MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

1

Aligning Incentives

Professional Writing in the

Army’s Operational Domain

Lt. Col. Jay Ireland, U.S. Army

Maj. Ryan Van Wie, U.S. Army

C

lear writing is an essential skil for Army leaders—

important to al, regarless of age, rank, branch,

component, or position. It benets soldiers while

serving and is an invaluale tool when transitioning to

civilian life. Using strong writing skils to contribute to

the U.S. Army’s professional dialoue is key to ensuring

a healthy ow of ideas and perectives across the force.

1

Saly, numerous Army pulications have suered in

recent years with decreasing article submissions, reader-

ship, and impact across the force.

2

Senior Army leaders,

including Chief of Sta of the Army (CSA) Gen. Randy

George, recently caled on al soldiers to return to more

intelectual rigor with professional writing, suporting dia-

loue on critical topics in professional Army pulications.

3

e newly launched Harding Project suports the CSA’s

uidance, seeking to reinvigorate U.S. Army professional

journals and making writing venues more accessile for

soldiers across the force.

4

A key to successfuly implementing the CSA’s uidance

is a robust suply of timely, wel-wrien articles from the

operational force. However, writing a professional article

can seem daunting for many soldiers. e nationwide

decline in writing skils is wel-documented, and schools

are less frequently mandating writing courses, including

at West Point.

5

While professional writing courses are fea-

tured in the U.S. Army’s institutional domain, covered in

most professional military schools, a soldier’s writing edu-

cation oen stagnates in the operational domain. e U.S.

Army’s fast-paced operational tempo and profuse tasks

create trade-os for soldiers and leaders who can only ac-

complish so much.

6

Varying education levels and writing

skils create further chalenges for unit leaders who would

like to create a writing development program. Given these

constraints and trends, how can a unit’s leadership develop

and incentivize professional writing in their organization?

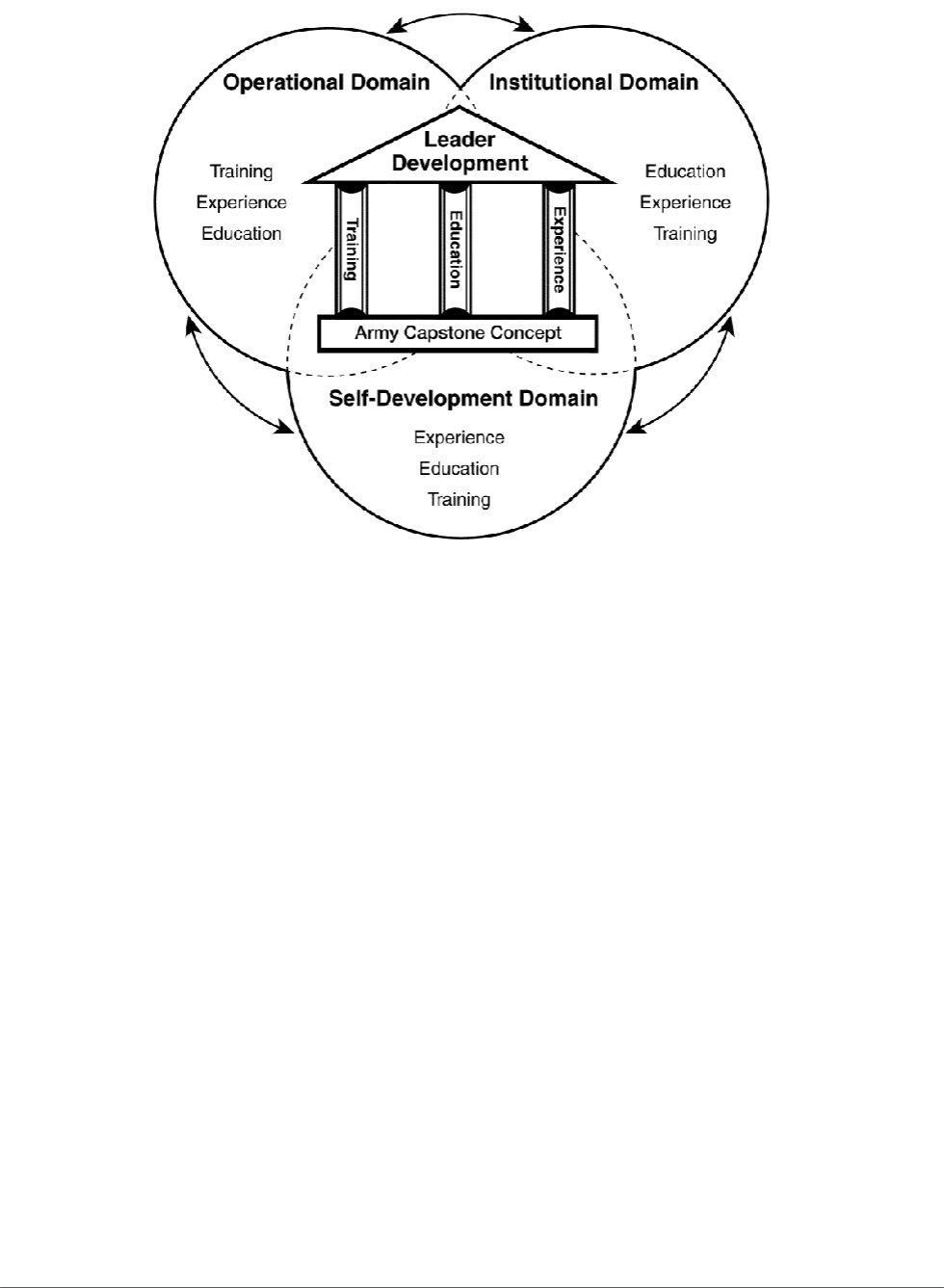

is article provides a way for a baalion to opera-

tionalize the CSA’s uidance and cultivate writing skils in

the operational domain. While the Army’s institutional

domain has lead on educating writing skils, we arue that

leaders in the operational domain need to do more to

improve their subordinates’ writing skils in accordance

with the Army’s leader development model (see the

ure). Professional writing deserves a central place in

every unit’s leader development strategy and needs to be

incentivized by commanders. Leaders at echelon can play

an important role in cultivating a subordinate’s writing

skils, creating unit-level writing development programs,

seing reasonale goals, mentoring authors through the

submission process, and most importantly—incentivizing

writing. More plainly, commanders should look to make

professional discourse “cool” in their organizations.

We launched the Mustang Writing Initiative in

January 2023, comprising a series of leader professional

development sessions, working lunches, writing work-

shops, and baalion internal peer-review sessions. With

concerted eort and command emphasis, seven Mustang

authors have pulished articles in professional journals

over the last year. Another six, including ocers and

noncommissioned ocers, have papers submied for

review or papers that are in various stages of development.

is experience shows Army leaders in the operational

domain can play an important role in developing their

PROFESSIONAL WRITING

MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

2

subordinates’ writing skils, fostering beer writers, and

suporting the CSA’s cal to write.

e Mustang Writing Initiative—How

It Started

As we mentioned, creating an eective incentive

structure aligned with professional writing helps produce

results in an era of competing demands on leader time.

What motivated the authors to write? e answer is

simple—we are in a business where the inability to do

one’s job can result in the unnecessary death of soldiers.

Combat experience as junior ocers was central to shap-

ing our professional outlook and worldview. Specicaly,

both of us have experienced a common occurence of

showing up to an area of operations to relieve a unit

from a mission only to realize that the previous team did

not write anything down about best praices or what

they learned. We came to understand the importance

and professional imperative of sharing the answers to the

test, eecialy when that knowledge came at the ex-

pense of soldiers’ lives. Writing serves to formalize those

lessons and memorialize the eorts of the thousands of

soldiers who came before. Units can fal into the trap

of immediately moving to solve a prolem they do not

understand without a professional discourse.

e Mustang Writing Initiative (hereinaer the

Initiative) was initialy pulished in our baalion’s

quarterly training uidance as part of the baalion’s

leader development strategy. e Initiative began as an

optional eort designed to suport any Mustangs inter-

eed in authoring a professional paper. e Initiative’s

expanded purpose was to improve Mustangs’ wrien

communication skils with tailored feeback, peer

review, and senior leader engagement. We deliberately

decided to make participation optional, acknowledging

that professional writing takes time and focus that may

not be availale for al soldiers in our formation.

Given these chalenges associated with professional

writing, we did not mandate pulication in a profes-

sional outlet as the only end state. Pulishing an article

in a U.S. Army journal was not a feasile rst step for

numerous volunteers who needed aditional writing

development. We acknowledged dierent education

levels and writing experiences among Initiative volun-

teers, and we had a broad denition for a “professional

paper.” Instead of only focusing on professional puli-

cations, we encouraged participants also to consider

pulishing an aer aion review (AAR) or a short

white paper intended to be shared across our brigade

and division.

Given an already busy bale rhythm, we conducted

monthly Initiative meetings as a working lunch to max-

imize aendance and limit scheduling conicts. Initial

meetings focused on identifying potential topics, devel-

oping thesis statements, conducting literature reviews,

creating outlines, and leveraging evidence. Aditionaly,

we oered short discussions about writing techniques

from sources such as Dr. Trent Lythgoe’s Profesional

Witing: e Comand and General Sta Coege Witing

Guide.

7

As authors developed outlines and draed pa-

pers, they received tailored feeback on working dras

from one of us (baalion commander or XO), along

with submission advice and recommended next steps.

As the Initiative has evolved, the monthly meetings

now entail the folowing:

•

We briey discuss recent professional pulications of

interest to the 1st Baalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment,

and recommend future reading.

•

Successful authors share their pulication experience

to include thesis development, evidence selection,

research process, outlet selection, and submission

lessons learned.

•

Working dra authors share an update on their proj-

ects, including curent dra status, literature review,

help needed, and goal outlet or product (e.g., AAR or

white paper).

Maj. Ryan C. Van Wie,

U.S. Army, is an infantry

ocer and the executive

ocer of 1st Baalion, 8th

Cavalry Regiment, 2nd

Armored Brigade Combat

Team, 1st Cavalry Division.

He previously served

in the 101st Airborne

Division (Air Assault) and

the 4th Infantry Division.

He holds a BS from the

U.S. Military Academy and

a Master of Public Policy

from the University of

Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Lt. Col. Jay A. Ireland,

U.S. Army, is an armor

ocer and commander of

1st Baalion, 8th Cavalry

Regiment, 2nd Armored

Brigade Combat Team,

1st Cavalry Division. He

previously served in the

1st Armored Division and

the 4th Infantry Division.

He holds a BS from the

U.S. Military Academy and

an MA in geography from

the University of Hawaii,

Manoa.

PROFESSIONAL WRITING

MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

3

•

We close the meeting with an oportunity for new

authors to share project ideas, ask questions, and

receive feeback from the audience on thesis develop-

ment, paper outline, and literature review help.

In total, this monthly working lunch lasts an hour,

and participants are encouraged to schedule folow-on

apointments as needed to receive focused assistance

with any steps in the writing process. On average, over

the last year, each of us inveed aproximately ten

hours into the Mustang Writing per month; those

hours comprised monthly group meetings, one-on-

one meetings, and time ent reviewing dra outlines

and papers. We’ve found this process to be an eec-

tive method to develop our junior writers, educate

participants about the research and writing process,

mentor volunteers through the submission process,

and hold authors accountale for completing dras.

Eleven Mustang authors who used this model over

the last year wrote nine professional articles, three

white papers, and two AARs that contributed to the

U.S. Army’s professional discourse and shared lessons

learned across the force.

In adition to the Initiative, we instituted a require-

ment for the sta duty ocer (SDO) to write an analyt-

ical essay during their twenty-four-hour duty. Using the

division and brigade commander priorities as a uide, we

selected articles for the SDO to read and write a one-page,

single-spaced essay asking the author to explain how the

selected article is relevant to their curent position. e

SDO then sends that essay to the baalion commander,

executive ocer, command sergeant major, and their

commander and rst sergeant. Feeback for the SDO

essay comes in the form of a note from the baalion com-

mander focused on the essay’s substance, the writing, and

recommendations to improve. Mustang ocers serve as

SDO once a month, meaning they wil write twelve essays

a year. e paper is a page in length, requiring ve minutes

to read and another ten minutes to type a response.

What We Learned

Foremost, a unit writing program takes time and

effort. Specificaly, it takes commander energy that is

already short in suply and in high demand. A more

professionalized and intelectualy curious team is

Figure. Army’s Leader Development Model

(Figure from Department of the Army Pamphlet 350-58, Army Leader Development Program)

PROFESSIONAL WRITING

MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

4

more lethal than one that does not engage in an ac-

tive dialoue about more effectively achieving read-

iness. We believe the writing program’s value comes

from the pride attained from completing the rigor-

ous process associated with professional writing and

the camaraderie that comes with working with peers

to make these articles hapen. A successful method

to ensure completion is to encourage coauthorship to

help share the burden as wel as further the network

of people thinking criticaly in the unit. This is even

more true when the authors are writing about new

and innovative ways of training ready formations

and employing new technology. Al of us have heard

young leaders complain about how stupid something

is—wel, why don’t they write about it and bring

about change?

Aditionaly, we are not advocating for everyone

to submit articles to professional journals. e ood

of papers would drown the already thin editorial

teams of our military journals, and the rigor required

for professional pulication is not necessary for ev-

eryone in the formation. We have found over the last

year that we do not strugle to nd people who want

to pulish. Most people feel they have nothing to

oer the larger community, are afraid of the backlash

associated with online trols, and/or feel that they

aren’t good enough to see something like this come to

fruition. It is our job as leaders to encourage and assist

those who are seeking professional development and

to show our people that we care.

Like al leader development efforts, the number

one key to success of any writing program is com-

mander participation and folow-through. If the

battalion commander is personaly writing an article,

participating in the program by sharing drafts (even

if they are underdeveloped and need improvement)

and taking feeback about how to best proceed

with their article, then others wil be encouraged

to dive in themselves. Our investment in the pro-

gram showed that we valued professional discourse,

enaling the program to take off with new authors

joining the Initiative every month. What started as a

handful of captains has evolved into a program with

al ranks including noncommissioned officers.

Another way to incentivize writing is senior leader

armation. Successful Army writing across the

force requires buy-in at echelon, with senior leaders

meaningfuly engaging with authors and continuing

the professional dialoue started in an article. Authors

wil be encouraged to continue professional writing

if they receive one email from a general ocer teling

them to keep going. Or from a baalion commander,

company commander, or rst sergeant who gained

something from the article pulished by a rst lieu-

tenant or sta sergeant. If an author ends months

rening an article and exercises personal courage by

opening themselves up to worldwide criticism only

to receive deafening silence, then it is reasonale to

assume that author wil never write again. Worse,

they may aively discourage those around them from

aempting professional writing.

Conclusion

e CSA and the Harding Project both note that

U.S. Army professional journals need to be revitalized to

strengthen wrien discourse and produce new ideas for

emerging operational concepts and technology. Writing

education in the U.S. Army cannot only exist in the insti-

tutional domain and professional military education. As

noted in the Army’s leader development model, education

continues in the operational domain (see the ure).

8

To

answer the CSA’s charge and create an aditional suply

of articles, the operational domain needs to do more to

foster professional writing in its ranks. We should not

alow our people to take complicated topics and boil them

down into one-slide concept of operations and instead,

A more professionalized and intellectually curious

team is more lethal than one that does not en-

gage in an active dialogue about more effectively

achieving readiness.

PROFESSIONAL WRITING

MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

5

encourage our people to write tight, inteligent papers to

communicate those ideas across a larger community of

engaged minds. Leaders at echelon can enhance writing

skils in their units by creating unit writing development

programs and incentivizing their soldiers to write profes-

sionaly. ough the force is chalenged by a busy opera-

tional tempo, an investment from leaders at echelon can

provide soldiers with the writing development they need

to meaningfuly engage in professional discourse, share les-

sons learned, rene doctrine, and prepare the U.S. Army

for the complicated operating environment of the future.

Finally, Congrats to ese Mustang

Authors!

Pulished and forthcoming Mustang Writing

Initiative Papers:

•

Lt. Col. Jay Ireland and Maj. Ryan Van Wie,

“Task Organizing the Combined Arms Baalion

for Success in Eastern Europe,” Military Review

103, no. 6 (November/December 2023): 35–44,

hps://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/

Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/

November-December-2023/Task-Organizing/

•

Maj. Ryan Van Wie and Dr. Jacob Walden,

“Excessive Force or Armored Restraint:

Government Mechanization and Civilian

Casualties in Civil Conict,” Journal of Conict

Resolution 67, no. 10 (2023): 2058–84, hps://doi.

org/10.1177/00220027231154446

•

Lt. Col. Jay Ireland, “Peaking at LD: A Way to Assess

Maintenance Excelence at the Baalion,” Aro

Magazine 135, no. 4 (Fal 2023): 25–28, hps://www.

dvidshub.net/pulication/562/armor-magazine

•

Capt. Lary Tran, “Manning the Next Generation

Bale Tank,” Aro Magazine 135, no. 4 (Fal 2023):

54–59, hps://www.dvidshub.net/pulication/562/

armor-magazine

•

Capt. Lary Tran and 1st Lt. Brandon Akuszewski,

“Tanks Need Infantry to Lead the Way,” Aro

Magazine 135, no. 4 (Fal 2023): 20–24, hps://www.

dvidshub.net/pulication/562/armor-magazine

•

1st Lt. Daren Pis, “Maximizing Operational

Readiness on EUCOM Rotation,” Aro Magazine

135, no. 4 (Fal 2023): 50–53, hps://www.dvidshub.

net/pulication/562/armor-magazine

•

1st Lt. Ben Kenneaster, “Sustainment Chalenges

in the Baltics and the Eects of LSCO,” Ary

Sustainent (Winter 2024): 59-62, hps://www.

army.mil/article/273300/sustainment_in_the_bal-

tic_states_and_the_eects_on_lsco_a_junior_lead-

er_perective.

•

1st Lt. Dan Slaton, “Operating Uper Taical

Internet in the High North,” Ary Comunicato

(forthcoming)

Current Mustang Writing Initiative

Working Dras

•

Sta Sgt. Austin Abadie, Sgt. Damien Kirven,

1st Lt. Ben Kenneaster, and Sta Sgt. eodore

Montgomery, “Braley Fighting Vehicle Lethality

Initiative: An SME Informed Method for Improving

Gunnery Results”

•

Sta Sgt. Cordel Wright, “Back-Ups to Belt-Fed

Machineuns”

•

Capt. Chris Smar, “Creative Baalion Religious

Suport during EUCOM Rotation”

•

Capt. Cam Waugh, “Analysis of the Armored Cavalry

Troop Performance during CBR XVIII”

•

1st Lt. Christian Arne, “Baalion LNO Experience

on EUCOM Rotation”

Notes

1. Army Doctrine Publication 6-22, Army Leadership and the

Profession (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Oce

[GPO], 2019).

2. Zachary Griths, “Low Crawling toward Obscurity:

e Army’s Professional Journals,” Military Review 103, no. 5

(September-October 2023): 17–28, hps://www.armyupress.

army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/

September-October-2023/Obscurity/.

3. Randy George, Gary Brito, Michael Weimer, “Strengthen-

ing the Profession: A Call to All Army Leaders to Revitalize our

Professional Discourse,” Modern War Institute, 11 September

2023, hps://mwi.westpoint.edu/strengthening-the-profes-

sion-a-call-to-all-army-leaders-to-revitalize-our-professional-dis-

course/.

4. Zach Griths and eo Lipsky, “Introducing the Harding

Project: Renewing Professional Military Writing,” Modern War

Institute, 5 September 2023, hps://mwi.westpoint.edu/introduc-

ing-the-harding-project-renewing-professional-military-writing/.

5. Michael J. Carter and Heather Harper, “Student Writing:

Strategies to Reverse Ongoing Decline,” Academic Questions 26,

no. 3 (Fall 2013), hp://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12129-013-9377-

0; Steve Graham, “Changing How Writing Is Taught,” Review of

PROFESSIONAL WRITING

MILITARY REVIEW ONLINE EXCLUSIVE · FEBRUARY 2024

6

Research in Education 43, no. 1 (2019): 277–303, hps://doi.

org/10.3102/0091732X18821125; National Center for Education

Statistics, e Nation’s Report Card, Writing 2011 (Washington,

DC: National Center for Education Statistics, September 2012),

hps://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pubs/main2011/2012470.

aspx#section1; “West Point Writing Program History,” United

Stated Military Academy, accessed 26 January 2024, hps://www.

westpoint.edu/academics/curriculum/west-point-writing-program/

history.

6. James Clark, “Soldiers Under ‘Enormous Strain’ Warn Ar-

my’s Top Enlisted Leader,” Army Times (website), 12 May 2023,

https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2023/05/12/sol-

diers-under-enormous-strain-warns-armys-top-enlisted-leader/;

Kyle Rempfer, “‘Got to Fix That’: Some Unit Ops Tempos

Higher than Peaks of Afghan, Iraq Wars, Army Chief Says,” Army

Times (website), 2 October 2020, https://www.armytimes.com/

news/your-army/2020/10/02/got-to-fix-that-some-unit-ops-

tempos-higher-than-peaks-of-afghan-iraq-wars-army-chief-

says/.

7. Trent Lythgoe, ed., Professional Writing: The Command

and General Staff College Writing Guide, Student Text 22-2

(Fort Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff

College, July 2023), https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/

home/Resources/CGSC-Professional-Writing-Guide.pdf.

8. Department of the Army Pamphlet 350-58, Army Leader

Development Program (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2013), 2.

US ISSN 0026-4148